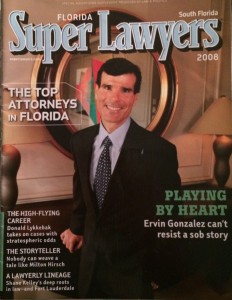

Ervin Gonzalez Featured on Cover of Super Lawyers Magazine

For Ervin Gonzalez to take a case, it has to pass the ‘wow’ test

Ervin A. Gonzalez’s heart still races every time he hears that knock on the jury room door signaling a verdict.

Never mind that he’s averaged about one million-dollar-plus win a year—including the largest personal injury award ever in a federal court (a $4.1 million jury award against a hospital accused of defrauding his client)—since his first one in 1988. Though Gonzalez had only been seeking $750,000, the hefty verdict didn’t surprise him.

That’s mainly because he was only three years out of law school.

“I didn’t know enough to know that that was a big deal,” confesses Gonzalez, 47. “I was just doing a job. If you get good facts, present a good case, you get good damages. That’s what lawyers do.”

Now a partner at Colson Hicks Eidson in Miami, Gonzalez’s resume could fill a tome. But his beginnings were humble. His parents emigrated from Cuba in 1960, shortly before Gonzalez was born, determined to raise their child in a free country. To make ends meet, his dad worked as a bellhop at the Jefferson Hotel on Miami Beach; his mom in Kensington Park Elementary School’s cafeteria. At home, the Gonzalez family incorporated the cultures, speaking both English and Spanish. When he wasn’t studying, Gonzalez played infielder for a local Latin-American baseball league.

It was his father’s preoccupation with what was happening in Cuba that shaped Ervin’s fierce dedication to the rule of law.

“When Cuba was taken over by tyranny and oppression, nothing could be done to stop it,” says Gonzalez, seated at a large wooden desk on the second floor of his boutique law firm in Coral Gables. Framed diplomas, certificates and accolades fill an entire wall; a photo of his wife, Janice, and their dog, Foxy, are tucked into his blotter. Focused but friendly, Gonzalez has a compact athletic build and short-cropped hair. He is the kind of guy you would expect to remember names, dates and places. When he speaks about clients who have been wronged—or about his country—his jaw sets with conviction.

“In the U.S., people respect the law,” Gonzalez says. “I love this country for its constitutional rights and due process. It’s meaningful to Americans, and I always knew, from the time I was really little, that I wanted to be a part of this legal system.”

So much so that he has never traveled to his parents’ native homeland: “Never, as long as [either] Castro is in power. I am not going to give him my hard-earned American cash so he can use it for his Communist ways.”

Gonzalez started making that hard-earned cash at a young age, working his way through La Salle, a private Catholic high school, as a bag boy at a local Winn-Dixie grocery store. He juggled several jobs—disc jockey, department store sales clerk and helper for mentally challenged children and young adults—while attending Biscayne College. Gonzalez earned a degree in political science and graduated in 1985 from the University of Miami School of Law cum laude. He worked for a local firm, Fine Jacobson Schwartz Nash Block & England, for three years before starting his own firm with attorney Karen Gievers. When she moved to Tallahassee, Gonzalez joined Colson Hicks Eidson.

The 15-lawyer firm handles only high-stakes, complex plaintiff-side lawsuits. Gonzalez chooses his clients carefully. His criteria? “The case has to pass the ‘wow’ test. If someone comes in here and explains something to me and I think, ‘That’s wrong, that’s not supposed to happen,’ then it’s a case I want to work on. For me, losing is not an alternative,” he says.

This philosophy underscores how Gonzalez approaches life: head-on. It also explains his passion for his job, as well as all his other activities. “If I fail, it’s not for lack of trying,” he says with a laugh. Every morning, Gonzalez gets up early to train in a triathlete discipline—running, biking or swimming—before heading off to work, but he doesn’t participate in triathlons. Such competition would consume him, he says, and he would rather expend his energy on his cases, and his involvement in the legal community. He is a member of the board of governors of The Florida Bar, the National Institute of Trial Lawyers and the American Board of Trial Lawyers; past president of the Dade County Bar Association and the Dade County Trial Lawyers Association, and former director of the Academy of Trial Lawyers.

Compassion counts

When Gonzalez takes on a case, he tries to see things from the client’s perspective. Gonzalez knows what it is like to experience trauma: His wife is a six-year breast cancer survivor. “If I represent someone, I have to understand their loss. I have to feel how they feel about it. I’m their champion. That’s the only way I can know in my heart what the real value is for that case.”

One such case involved the 2005 medical malpractice suit against Mayport Naval Station. The hospital was found guilty of medical negligence in the childbirth of Kevin Bravo Rodriguez, who was born with severe brain damage. The parents were awarded $60.9 million. Although that was later reduced to about $41 million, it was still a record for a case tried under the federal Tort Claims Act, which deems that all cases against the U.S. government must be decided by judges, who typically award smaller amounts than juries.

Gonzalez—along with Coral Gables lawyer Deborah J. Gander—argued that the hospital staff was grossly negligent, ignoring evidence of fetal distress during the childbirth. Kevin was finally delivered in an emergency Caesarean section. He requires around-the-clock care and cannot speak, hear, see, swallow or move, although he can feel pain.

Earlier that same year, Gonzalez won a $65 million verdict (including $61 million in punitive damages) for the family of a 12-year-old boy who was electrocuted after taking refuge in a lighted Miami bus stop during a late-hurricane-season storm in October 1998. Although the defense argued that lightning killed the sixth grader, Gonzalez maintained that Jorge Luis Cabrera died as the result of inadequate electrical work done by an outdoor advertiser, Eller Media.

This case had already been tried by a criminal jury, which found Eller Media not guilty. But Gonzalez prevailed in civil court, where the burden of proof is different and witnesses are required to testify. In criminal trials, a witness can cite the Fifth Amendment, which guarantees against self-incrimination. When Gonzalez—along with Colson Hicks Eidson partner Bob Martinez—questioned Eller Media, he says the officials admitted they had not adequately supervised their employees. Electricians themselves confessed that their work was below standard, he says, and one testified that he had not installed proper fuses, did not use an approved electrical box and had cut grounding rods in half. Furthermore, says Gonzalez, he was not a licensed electrician.

After nine years of preparation—the criminal trial had to run its course first-the civil trial lasted nine weeks, but it took only two days of deliberation for the Miami jury to find Eller Media responsible for Jorge Luis’ death. Further investigation by the county into the company’s operations and maintenance of Miami-Dade Transit Authority bus shelters revealed that more than 100 had been improperly wired and lacked proper permits and/or inspections. As a result, most are now lit by solar panels mounted on the shelters’ roofs.

Jorge Luis’ father says that, though he can never get his son back, what Gonzalez did was the next best thing. “He’s an excellent person, very professional and with a very big heart,” says Jorge Cabrera, his voice choked with emotion a decade after his son’s death. “He became like family; when I talked to him, it was [like] talking to my brother. We’re still in touch—two years later—that shows that it wasn’t just about the case.”

One of the lawyers who went up against Gonzalez in the Eller Media case is Mark Seiden, who won the criminal case but lost the civil suit. Seiden, also on the Florida Super Lawyers list, has nothing but praise for his adversary: “He is among the top tier of the finest lawyers that I’ve ever had the opportunity to litigate against. He is very aggressive, very prepared and very much a gentleman.”

Another Gonzalez victory, this one in the form of a settlement, contributed to the overhaul of Houston-based funeral chain Service Corporation International (SCI), the world’s largest funeral operator. The company was accused, in the first of several class action lawsuits, of numerous violations, including desecrating Jewish cemetery sites in South Florida, misplacing and replacing bodies and overselling plots.

The lawsuit was settled in part to avoid the trial concerning the case of Hymen Cohen. Rather than follow in the tradition of decorated war heroes buried in Arlington Cemetery, Cohen chose, for religious reasons, to be buried near his family in Menorah Gardens cemetery in West Palm Beach, owned by SCI. Gonzalez says it was only when an employee who knew about the practice of dumping bodies in the woods blew the whistle that the scandal became public and the Cohen family learned they had been visiting someone else in Hymen’s designated spot.

Gonzalez, co-counsel (along with Neal Hirschfeld) for the plaintiffs, helped bring to light egregious violations that had taken place at Menorah Gardens & Funeral Chapels. Employees moved headstones, broke into vaults to squeeze in other burials, removed bones from broken vaults and discarded them, and in one instance buried two babies in a single grave.

The plaintiff was willing to settle for $100 million, but the defendant refused. Only when jury selection began did the defendant agree to the settlement—plus another $17 million to fix the problems at two cemeteries.

After Hurricane Andrew devastated South Florida in 1992, Gonzalez was co-lead counsel seeking compensatory damages for homeowners in Country Walk, a development in one of the hardest-hit areas. Several hundred homes and condominiums were destroyed; homes folded like matchboxes. An investigation by engineers hired by the plaintiffs reported building code violations, poor workmanship and inferior materials. “There were no hurricane anchors in the roofs, and the homes weren’t built using proper material,” Gonzalez says. “This settlement created awareness and breathed life back into the community.” In the wake of this case, Florida implemented statewide building codes that have influenced national standards.

Role models

Gonzalez’s mentors over the years have included four outstanding trial lawyers with whom he worked at Fine Jacobson Schwartz Nash Block & England: Irwin Block, Gary Brooks, the late U.S. Magistrate Ted Klein and Joe Serota, now of Weiss Serota Helfman Pastoriza Cole & Boniske. “They taught me how to be a lawyer,” he says. “Law school teaches you how to think in a practical way, but they taught me everything else I needed to know.” He teaches others as an adjunct professor at the University of Miami Law School.

But when it comes to work ethic, Gonzalez is following in his father’s footsteps. At 78, his dad still works at a shipping company. The younger Gonzalez does take family vacations, but he admits that, after a few days on the road, “the [work] bug takes over.” To help achieve a balance, he sometimes takes his Intrepid 323 out on the water near his house. When he has more time, he heads for the ocean on his 44-foot Ocean Yachts vessel. But if he’s staying home, he likes to play his guitar to relax. Gonzalez jokes that his wife of 20 years takes their dog for a walk as a reprieve from listening to him play.

Gonzalez is also very active in the Church of the Little Flower, where he chaired the parish’s fund-raising campaign for the Catholic Church’s equivalent of United Way. He is on the board of trustees for St. Thomas University and does pro bono work as a guardian ad litem for the 11th Circuit. Judges appoint him to review cases involving children, to make sure the youngsters’ best interests are considered. “There are a lot of judges, and if each one sends me a case, I average about 12 to 15 a year,” he says. “I never say no.”

To keep it all under control, Gonzalez has a system: Each Monday, he outlines on his legal pad what he wants to accomplish for the week, then breaks it down into each day. “To be a successful trial lawyer, you have to be organized,” he says. Only when all the items for the day have been checked off does he give himself permission to switch gears and head home.

Not that he minds working late. When Gonzalez talks about work, he becomes animated. His perfect day? “Trying an extremely important case with high stakes. I’m fulfilled in that role, to do something for others. I have a purpose in life. Truly. It’s what I live for and what I was born to do.”

His heart keeps on racing as he waits for that next knock.